A project of personal musical formation.

One of the books I’ve most enjoyed reading the last few years was Brad Mehldau’s Formation: Building a Personal Canon Part I (I eagerly await the publication of Part 2). It is a remarkable memoir that weaves together his own life story up through his 20s with the experiences of music that formed him into the musician he is. With incredible forthrightness he chronicles the bullying of his childhood, the sexual assault he experienced at the hands of his high school principal, the many years of coming to grips with this through risky sexual activity, then his descent into a heroin addiction that dominated his 20s. It is not an easy read, but he manages all of this without being prurient or self-pitying.

Throughout he writes beautifully and insightfully about experiencing music from his earliest memories to playing in NYC clubs as an emerging force in the modern jazz scene.

Reading it has helped me reflect on my own musical formation a bit. The most influential forces in my life as a musician have been albums that captured my attention and drew me into their world over and over again, making irresistible the draw to make a life in music. Most of these were recordings, many were scores I played, and a very few were live performances. By far the larger part were recordings. This project is a look back at some of the albums that were most important to me as I grew up.

Part I: Introduction, A Life of Listening

I believe there have been two great historical declensions in Western music: before and after the development of notation and before and after the invention of recording. Of these two, I would argue that recording is a much more impactful invention. If nothing else, it has had a broader impact since it is not just a technology for composers and performers but for everyone who enjoys music.

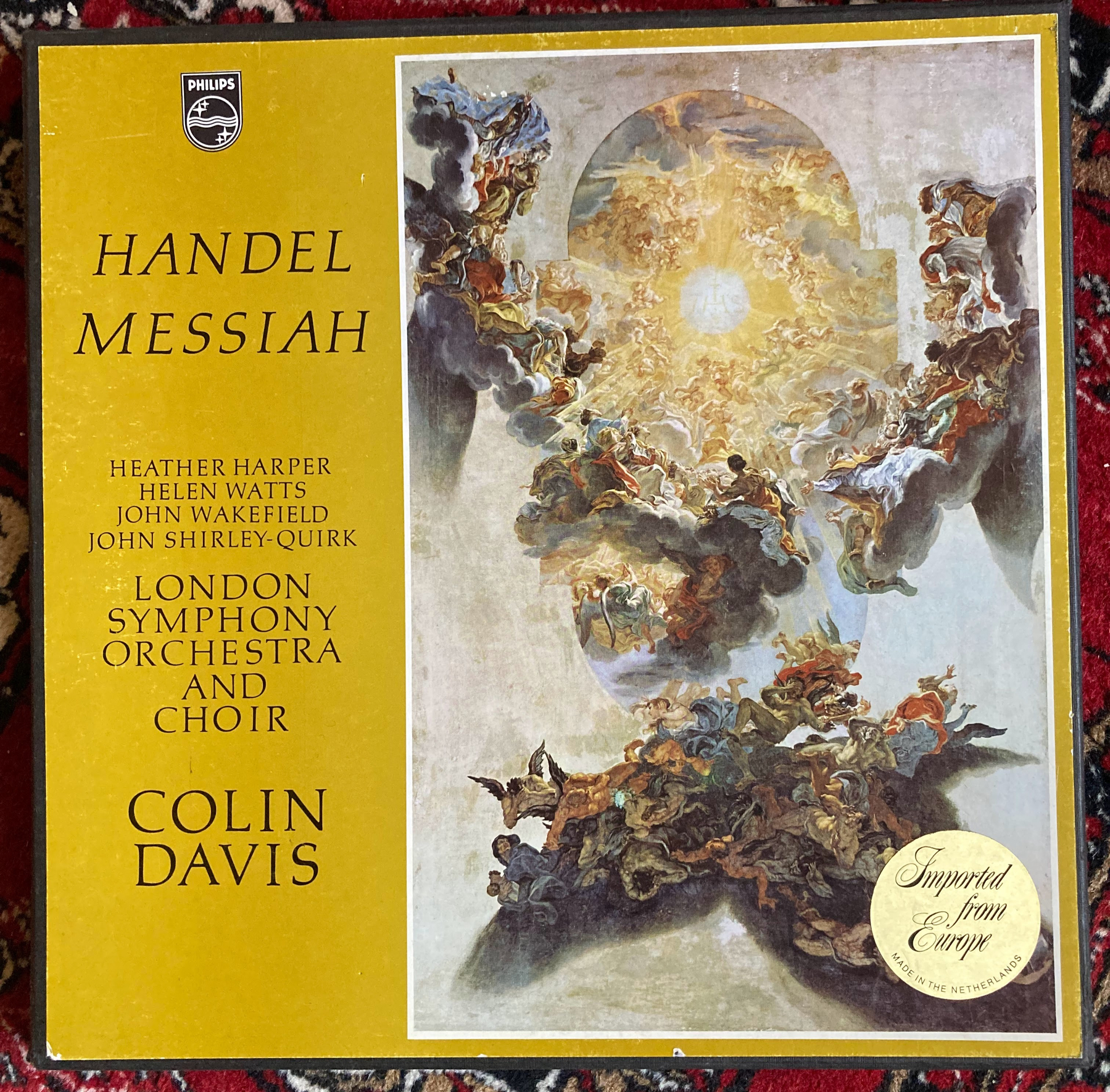

For someone who grew up relatively far away from the centers of culture, recordings were the key to my musical formation. I started listening to music before the iPod, so CDs were my first way into music. With limited access to the internet (and too many scruples for piracy), a BMG membership was my portal to the world of sound. The hours I spent agonizing over what albums I would choose for my monthly $6.99 cd, or a 12 for $3.99 each deal. The chores I did so that I had the money to spend on these!

Christmas of 2007 brought me the 30GB iPod Video. This didn’t change my relationship to CDs as much as make them much more portable. From this point on I was listening to music all the time. There is some music I purchased digitally (before the Starbucks gift card was a standard small gift the iTunes gift card was preeminent), but the music I really absorbed almost all came to me on CDs, which I ripped to my computer, organized and labelled (the earliest iTunes couldn’t download track information, you had to sit there with the jewel case or liner notes and type in each track!), and synced to my iPod. This syncing of course required a cord, because the iPod video could not access the internet. This was a ritual of near religious importance to me.

I had it in white. It shipped with the worst headphones ever devised.

In my teenage years I was generally either playing basketball, playing the guitar, or listening to music while doing something else. An enormous advantage of being homeschooled was that I had music going basically all the time while doing schoolwork. It also meant I could do my school work quickly and leave more time for basketball and music. Even with that extra time, I was most often practicing from about 10PM-12 or 1AM. This was partly personal preference and partly that during sports seasons the days were just very full.

This was also before any kind of streaming service was available, so the music you had available to listen to was owned or borrowed. Our tiny public library had a remarkably good selection of contemporary classical records curated by one of the libarians who had very hip tastes (nearly a whole shelf of Argo, Bis, Nonesuch, and ECM New Series recordings). In a full circle moment, a few Christmases ago I was visiting and took my kids to the library to play in the children’s area (it was freezing cold outside). By the entrance was a table of CDs being given away for free. Gavin Bryars, Michael Torke, Alfred Scnittke, many of the same CDs I checked out as a high schooler were there with date stamps in the mid-2000s as the last time they circulated. That is to say, before they became part of my permanent collection I (or one of my brothers) was the last person the check them out.

So whenever the mood strikes me, I’m going to go to my record/CD cabinet and pull out something that was a huge deal to me as a kid and write a bit about it. I don’t have a list, I’m just going to follow my gut and my ear.